This piece is the edited version of a “lightning talk” I gave to the Palinode team as part of our Khorafest retreat in August 2025. It is also available in podcast form and video.

Let me introduce one of my favourite thinkers, Murray Bookchin - the author of The Ecology of Freedom, best known for introducing the idea of social ecology. According to his theories, the natural world is inseparably tied to what happens in human society, so much so that if humans are to change their relation with nature, it is essential to look first at how humans relate to other humans.

Attempting to develop a philosophical framework for ecology through a radical left anarchist standpoint, Bookchin neither romanticises nature nor delineates it as something standing in opposition to human social development (Gaia theory for the former or “we are the virus” for the latter), but argues that a dramatic rethinking of our social structures is the only way to honestly address the current ecological crisis.

While this book is somewhat dated, the ideas that Bookchin introduces are incredibly powerful and translatable into the field of inquiry that interests me the most - a sort of networked ecology of technology.

Wholeness

Like any good Marxist, Bookchin begins to sketch a conception of wholeness by drawing from Hegel. Intimidating, but let’s have a read!

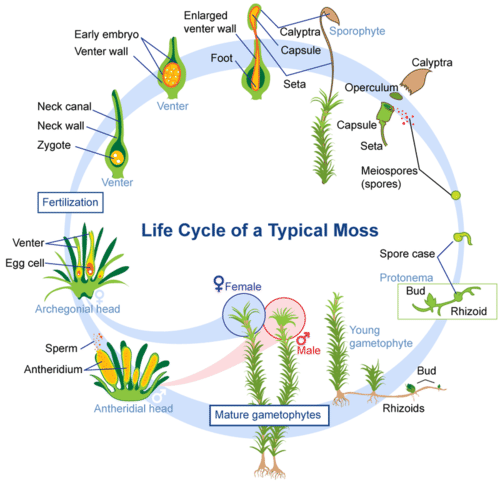

By wholeness, I mean varying levels of actualization, an unfolding of the wealth of particularities, that are latent in an as-yet-undeveloped potentiality. This potentiality may be a newly planted seed, a newly born infant, a newly born community, or a newly born society. When Hegel describes in a famous passage the "unfolding" of human knowledge in biological terms, the fit is almost exact:

The bud disappears in the bursting-forth of the blossom, and one might say that the former is refuted by the latter; similarly, when the fruit appears, the blossom is shown up in 'its turn as a false manifestation of the plant, and the fruit now emerges as the truth of it instead. These forms are not just distinguished from one another, they also supplant one another as mutually incompatible. Yet at the same time their fluid nature makes them moments of an organic unity in which they not only do not conflict, but in which each is as necessary as the other; and this mutual necessity alone constitutes the life of the whole.

I have turned to this remarkable passage because Hegel does not mean it to be merely metaphoric. His biological example and his social subject matter converge in ways that transcend both, notably, as similar aspects of a larger process. Life itself, as distinguished from the nonliving, emerges from the inorganic latent with all the particularities it has immanently produced from the logic of its most nascent forms of self-organization. So do society as distinguished from biology, humanity as distinguished from animality, and individuality as distinguished from humanity. It is no spiteful manipulation of Hegel's famous maxim, "The True is the whole," to declare that the "whole is the True." One can take this reversal of terms to mean that the true lies in the self-consummation of a process through its development, in the flowering of its latent particularities into their fullness or wholeness, just as the potentialities of a child achieve expression in the wealth of experiences and the physical growth that enter into adulthood.

Overall what we can gleam from this quote is a subtle, but powerful difference between Wholeness and One-ness. Bookchin continues:

We must not get caught up in direct comparisons between plants, animals, and human beings or between plant-animal ecosystems and human communities. None of these is completely congruent with another. […] It is not in the particulars of differentiation that plant-animal communities are ecologically united with human communities but rather in their logic of differentiation. Wholeness, in fact, is completeness. The dynamic stability of the whole derives from a visible level of completeness in human communities as in climax ecosystems. What unites these modes of wholeness and completeness, however different they are in their specificity and their qualitative distinctness, is the logic of development itself. A climax forest is whole and complete as a result of the same unifying process-the same dialectic-that a particular social form is whole and complete.

When wholeness and completeness are viewed as the result of an immanent dialectic within phenomena, we do no more violence to the uniqueness of these phenomena than the principle of gravity does violence to the uniqueness of objects that fall within its "lawfulness."

Here, Bookchin calls for a world where unique individuals get to develop their “latent particularities” into a collective wholeness. The utopian goal laid in front of us takes the shape of a climax forest, an example of what’s broadly known as an apex ecosystem. Such an ecosystem is a system in which all constituent parts have developed their latent potentialities - in other words, they have found their niche. While countless changes and developments take place all the time, such ecosystems become incredibly stable and resilient. Think of an old-growth redwood forest - precisely because of its diversity and high differentiation, can it not only survive through fires, storms and other catastrophes, but thrive in such competing multiplicity.

Dialectic as information exchange

But the question begs to be asked - if the strength of an ecosystem lies in every part of it being unique and different, how can we even talk about the ecosystem as a single thing? Where does the climax forest begin and end? What belongs to it, and what doesn’t? Taking stock of the forest’s constituent parts, trees, bushes, rocks, soil, fungi, birds, air, streams of water, fish, people, we would not manage to find anything that unites them all into some sort of oneness.

Strikingly, Bookchin says that it’s the process by which the ecosystem approaches wholeness that really matters. Such a process is facilitated not by the will of any individual, nor by divine design, but by a certain set of mechanisms. If organism A develops into organism B, we can think of this transition as a form of communication, a transfer of information between one state and another.

To make any kind of communication work, i.e. for it to be comprehensible and effective, there needs to be some structure, such as. a language, a rhythm, a harmonic progression. In other words, there needs to be a protocol.

WWW

We can think of protocols as agreements about information structure. They are not unlike languages - ways of assigning meaning to specific sequences of letters, so that both the producer and receiver(s) of information understand what is being said. Protocols make communication predictable and efficient. Consider one protocol we encounter almost daily - the Official Letter protocol. People have agreed to write official letters in a particular way, so that when I, as a receiver, first take the letter out of the envelope, I am immediately presented with the most important information - who sent it, who it's addressed to, and what it's about. Breaking the protocol is possible (and may even be desirable), but in most cases, everyone benefits if the protocol is respected.

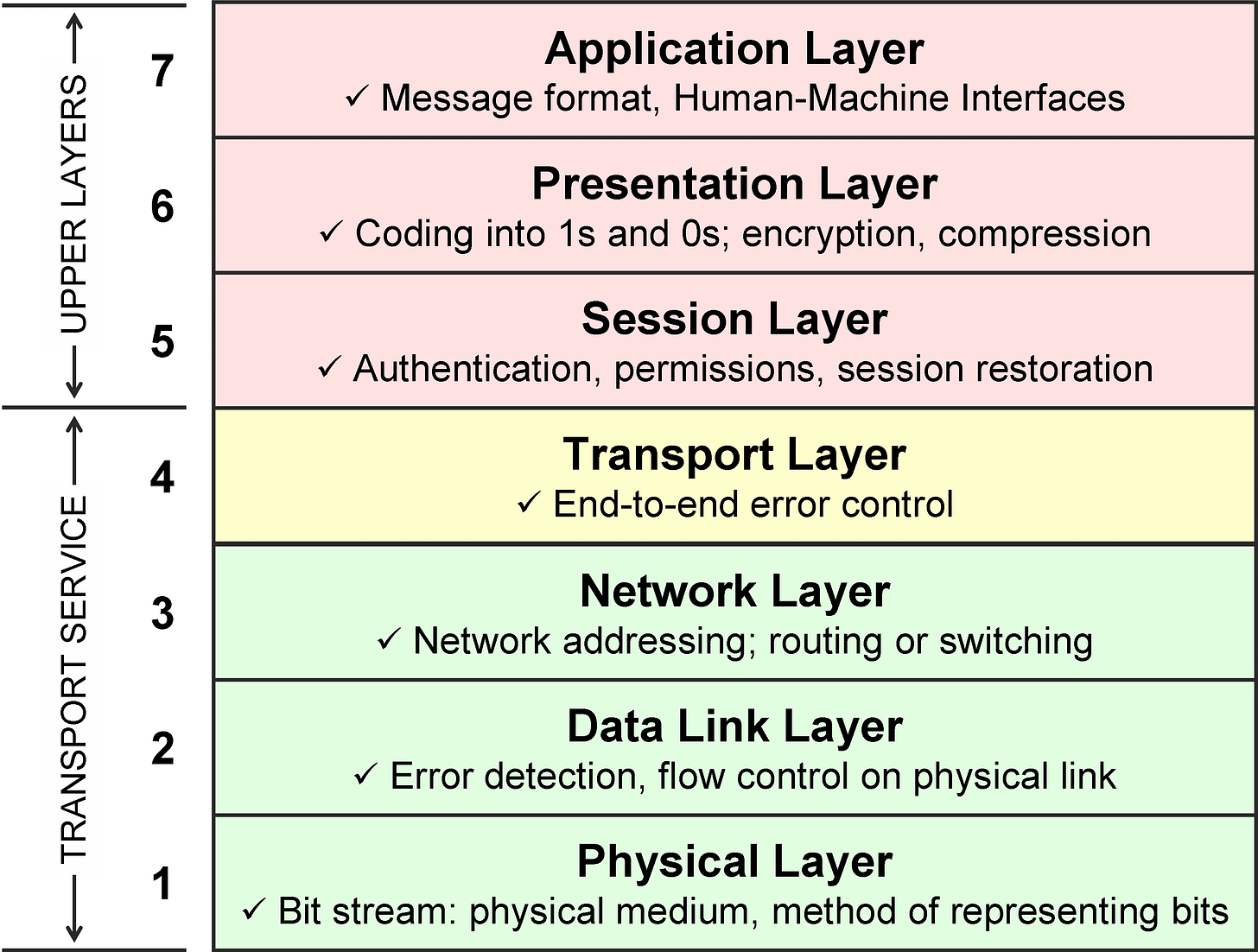

It is through protocols that the Internet was born, too. What we consider the invention of the Internet was really the introduction of a small set of protocols called the World Wide Web. Most of the protocols used on the Internet have either existed before the WWW, or have been added later. Together with these other protocols, the WWW completes what we call the Internet’s “protocol stack,”, also known as the OSI model.

It’s not essential here to understand what these layers stand for. All you need to know is that each layer has a protocol, and they get more and more “high-level,” or closer to what we as users actually perceive when we hop onto the WWW. The layers also get more powerful in terms of what you can achieve. While the physical layer literally just determines how electron flow down a cable is interpreted as signals, the application layer defines (among many other things) how the computer receiving a web page should render it on screen.

The original use case for the World Wide Web was for scientists to access each other’s documents from anywhere in the world and link them together in a massive web. The protocols enabling this are called HTTP and HTML, and they are really good at documents with links to other documents. They are not universal - they cannot express all human creativity, they do not allow for the “latent potentialities” of the Internet to flower.

However, they have one very important property - they are open standards, maintained by a consortium of public and private interests, and developed with input from the entire Web engineering community. As individuals within the Internet’s ecosystem try the protocols and discover what they’d actually like to do with them, they have the chance to influence the very protocols themselves. What we get is a sort of generative feedback loop between technology makers and technology users which results in a flourishing of colour, tone, harmony, dissonance, rhythm.

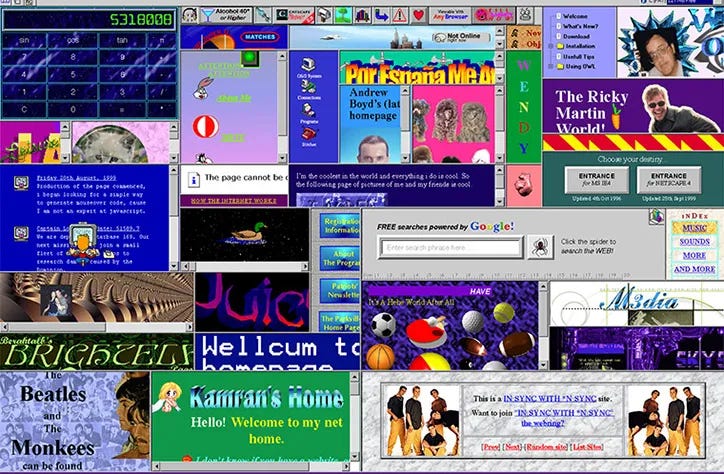

The barrier for entry was never negligible - creating a place on the internet almost always involved some programming, even though tools quickly appeared to build HTML pages without such know-how. What this meant was that every time someone opened Notepad and wrote <h1>Welcome to my website</h1>, they wound up releasing a unique and entirely different species into the ecosystem.

The protocol might dictate some structure to what you create, but it doesn't determine it. You are still free to break the rules in any way you see fit, and hope the message reaches someone - and boy, did people break the rules! Importantly, once the new entity is out there, it is entirely at the author's discretion to form and shape it. The organism grows, breaks, twists and turns, bright GIFs jump in and out of alignment depending on what browser/screen/device/drug you’re on.

Over time, some of the organisms begin to connect, forming symbiotic groups such as webrings (circular structures where you can only navigate to the previous or next site), indexes (linear lists of links) and portals (structured groups of indexes). Once search engines appear, they present a sort of teleportation device around the Web, but it is still useful to follow links from one site to another. The diversity of the ecosystem keeps increasing.

Another important property of Internet protocols is they are machine-readable. This means computers can serve websites which read other websites, programs like “agents” can crawl around the web. This makes any information available on the open web part of a kind of informational commons, a commons that enabled the success of LLMs.

To sum up, in theory the Internet ecosystem is:

democratic, because its protocols are open

organic, because its structure emerges through free action of its constituent parts, which act upon themselves and also each other

whole, because the constituents are free of hierarchies that would place one of them above another

Murray Bookchin would like this Internet. Unfortunately, while we are still using the same protocols, and that apex ecosystem still exists, over the decades a number of things have changed.

PageRank

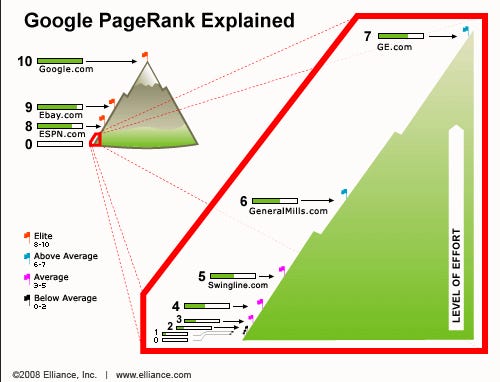

Google's greatest innovation was an algorithm called PageRank. The problem with search engines in the 90s was that just because a website contained the word "palinode," it might nonetheless mean the results were irrelevant for a user searching for "palinode productions." Just like a single tree doesn't make a forest, a single website without its context, does not yield a viable or suitable connection to your query. Furthermore, if you were just searching with keywords, website authors discovered that they can trick users by including thousands of keywords on every page, meaning you always stumble upon useless stuff regardless of your search term.

Very simply put, PageRank was innovative because it utilized the exact thing that made the Internet work - the idea of 'hypermedia' or linked documents - to rank websites based on how many other websites contain links to them. This is amazing for users, and it has been working for almost three decades. However, because of Google's near-monopoly on the search market, websites now have an incentive to do everything they can to please the PageRank algorithm. Over the years, Google added many other ranking mechanisms, which ultimately led to the internet becoming more uniform, standardised, unsurprising. That’s not necessarily always a bad thing - but the point is, it took away the democratic, organic agency of the ecosystem’s constituent parts to shape the greater whole.

The ecosystem began to change: instead of an old-growth redwood forest, we ended up with something more like a German pine plantation churning out dead Christmas trees instead of new life.

Walled Gardens

Enter now another shift in processes to the technological ecosystem; the rise of a bunch of technologies that allow very complex interactive applications to be built within websites. When this technology first appeared, people lauded it as Web 2.0. Now we have a web of exciting, lively experiences, replacing the dull linear websites (which ignores the fact that Web 1.0 sites did not have to be linear or dull). This influx of novelty coincided with the aftermath of the dotcom bubble as hundreds of Internet companies were wiped out. As a result, a few big predators appeared in the ecosystem and began to dominate.

Recall that these new hegemons walked into the forest of the web and everywhere they looked, they saw inconsistencies, UX issues, and most of all, wasted profit potential. With Web 2.0 technologies, companies like Facebook were able to create smooth and pleasant web sites which, despite being bland and artless, had enough interactive content to keep you interested for hours, day after day, year after year. Who’d have thought that a bunch rectangular interfaces wrapping dopamine-inducing multimedia content was what everything would become?

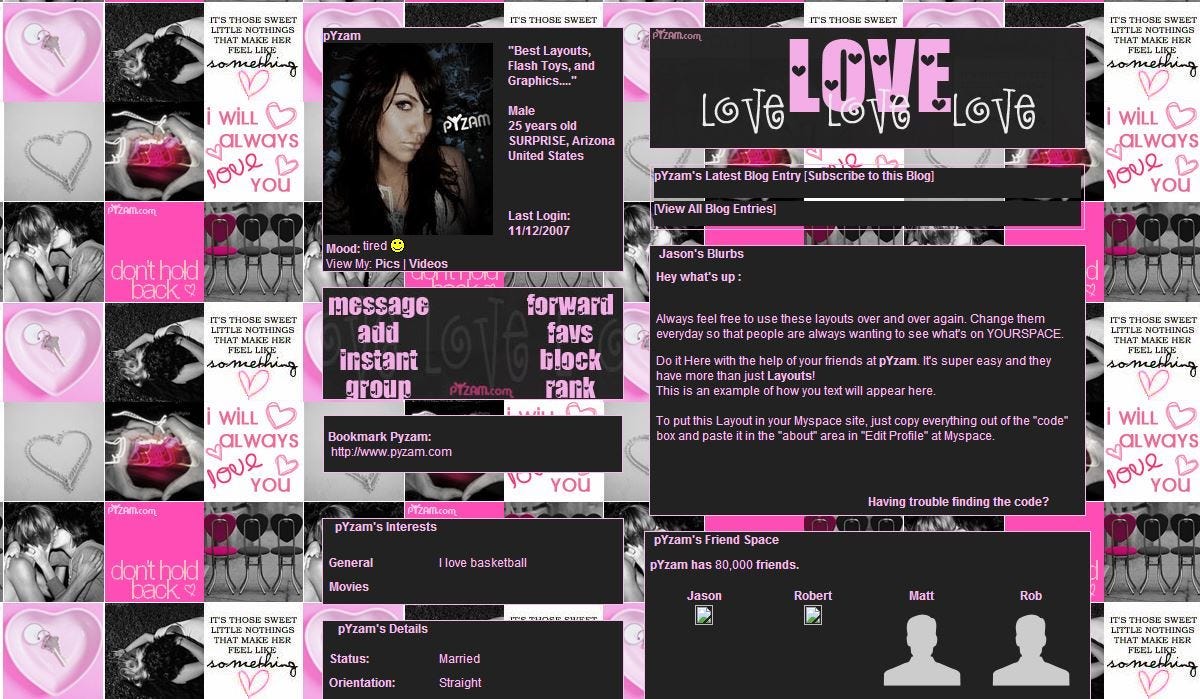

To be fair, platforms which attempted to return to the diversity of the early Internet – remember Myspace! – experienced brief success, but were and still are being steamrolled by Facebook and Twitter, ultimately becoming targets of mockery. The future belonged to Clean Code and minimalist design aficionados.

Small acts of rebellion – be it Instagram grid art or conceptual Twitter profiles – had a heyday, but eventually they too slid out of cultural relevance. Many of the creative techniques people would develop for a particular iteration of a platform would be eliminated on the whim of a product manager somewhere in Palo Alto (see Vine).

Apps

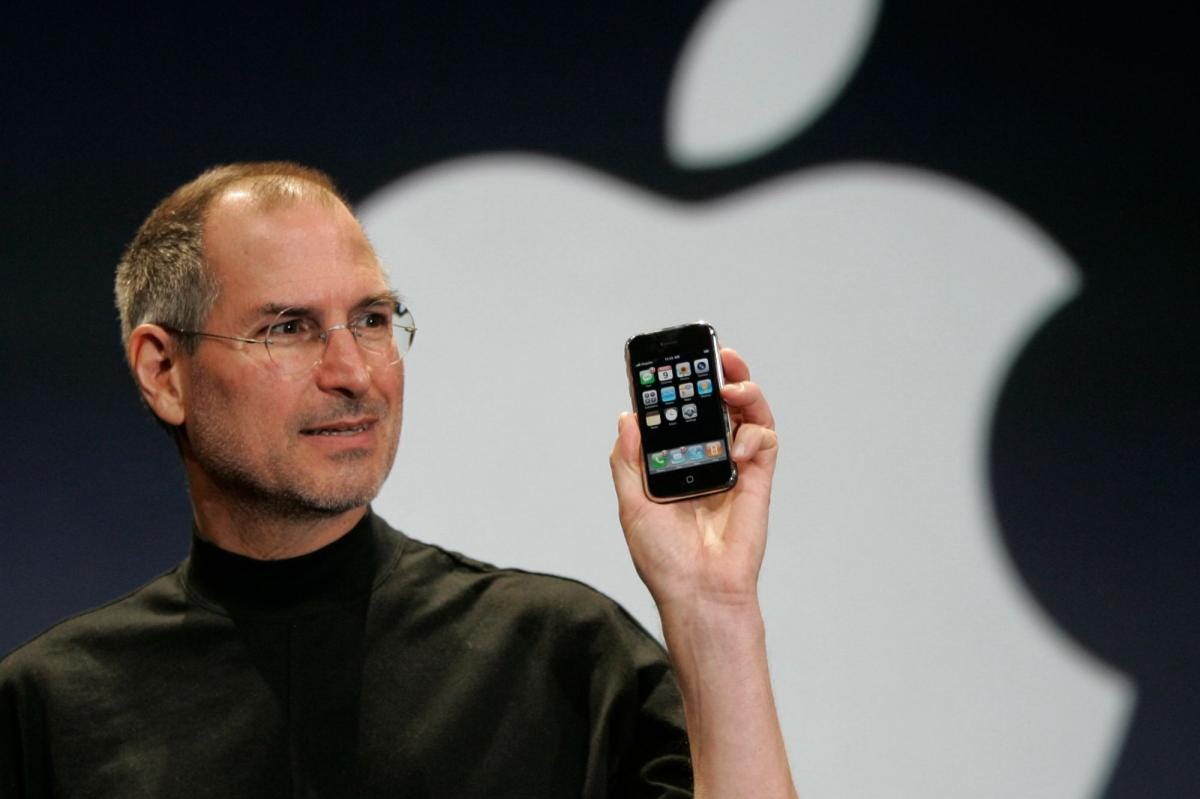

Another paradigm shift occurred not so long after Web 2.0 was introduced. With the release of the iPhone, Apple made a clear statement that native mobile apps were the future, and the internet would be relegated to “what isn’t an app… yet!”. This was great for Apple, business boomed as 30% of purchased apps went straight to Cupertino.

Before the iPhone, Apple had created a fantastic browser called Safari. It was fast, reliable, and stuck faithfully to the open Web standards. However, once they had an incentive to get people off the Web and into phone apps, the development of Safari slowed down. Many non-standard features appeared while adoption of new open standards was quietly pushed to the back burner. These days, Safari like Internet Explorer has simply become another inferior piece of tech forced onto people by a domineering tech giant, the predator ravaging the sustainability of our ecosystem.

You might wonder - but Instagram is an app, and also connected to the Internet. What makes it so different from Instagram the website? Well, again it comes down to the protocols. While Instagram uses the World Wide Web protocols behind the scenes, the app we access as users is made of custom, closed-source, non-standard code. You can only access Instagram using the code Instagram tells you to use.

This also means you can't choose how instagram will be presented to you - would you like to configure the app so it doesn't show you the addictive, dopamine-inducing Reels? You would be able to do this in a web browser with a browser extension, but in the app? Tough luck! You will watch the Reels because Daddy Zuckerberg wants you to.

As we've shifted from open protocols to closed apps, many things that used to be possible with technology became impossible. For example, messaging services such as iChat, Google Chat, and Slack used to support open messaging protocols. This meant you could use iChat to talk to people on Slack, you could fire up an ancient IRC client and post messages onto Google Chat. It all worked much like phone calls or SMS - people agreed on an open standard, and you didn't have to worry if you're on a Motorola, a Samsung or an Ericsson.

With the app-ification of messaging, such streamlining is a thing of the past. You now have to maintain 4 or 5 messaging apps because for each of them, you have 1 or 2 friends who aren't on other apps. Is this what market-driven efficiency looks like? Who is winning here?

The combination of search engine ranking, Web 2.0 walled gardens and app-ification has turned our German Christmas Tree farm, still an ecosystem but less complex than the unruly forest, into a Mid-Western cornfield, near-identical stalks lined up in straight lines, waiting for their value to be extracted.

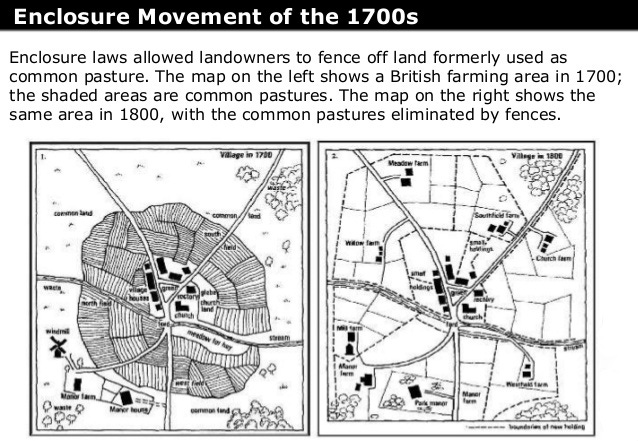

Interestingly, this erosion of diversity has striking similarities to the beginnings of capitalism in Britain when wealthy landowners began a violent process of *enclosing* what was called the commons, an area of land established by medieval communities which guaranteed that every citizen of the community had access to nature. As capitalism rose the uber rich took. over the commons and fenced it off from the public. The consequence was the creation of an impoverished, landless underclass which then went on to seek livelihood in the fledgling manufacturing towns. Industrial capitalism was born from the destruction of common spaces where uniqueness and diversity are a thing of the past.

The Resistance

Fortunately, there are lots of people who have realised the danger of such an enclosure, so I’d like to close by discussing a few of such movements.

Don’t trust me, bro

I’ll start with one that, in my opinion, got it somewhat wrong. In the cryptocurrency scene of the early 2010s, an idea spawned: the walled gardens of Web 2.0 could be abolished, but not with the old 90s protocols. Instead, what we need is a new set of blockchain-based protocols, seemingly more powerful, because they remove one very important aspect of the previous protocols – the requirement to trust the Other. The new Web - Web3 - would be a completely different beast, algorithmically safeguarding the freedom of its constituents, so that the walled gardens are mathematically impossible to build. However, in practice, the vast majority of Web3 looks a lot like this:

I can only speculate why that is, but my feeling is that the protocols of Web3, (having emerged from cryptocurrency communities) are fundamentally not designed for the kind of boundless creativity that might lead to a revival of an apex ecosystem. For example, specifically art-focused protocols like fxhash, abound with color and canvas but when you browse through, you find a flood of fairly homogenous themes and symbols. The platform places artworks in neat squares, surrounded by blockchain data, wrapped into a sleek black and white UI. On fxhash, there’s a very specific idea of what art is, and what it can be. Once again, we are given the old Web 2.0 – fenced-off cornfield, rather than a thriving ecosystem.

Crucially, FXHash art exists on FXHash. How does it interface with the rest of the Internet? How can it breed, ooze through, entangle itself with other things in the network? That doesn’t seem to be the focus here. Instead, we get an exclusive club of speculating art collectors and creatives pandering to the whims of the platform. Just like the old Silicon Valley walled gardens, Web3 seems to replicate the same cynical insistence on individualism and hierarchy.

Federatin’

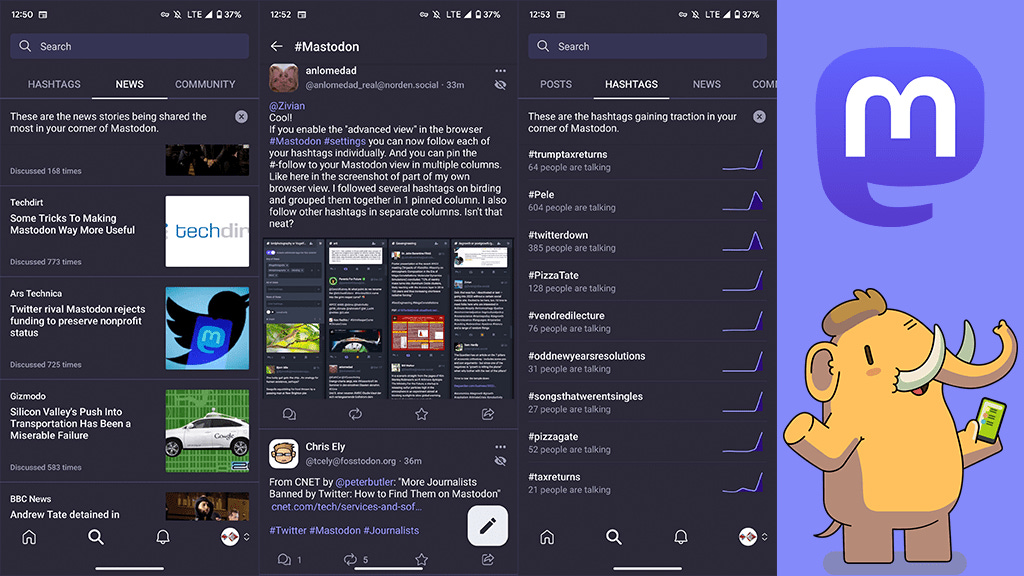

A much more successful method of addressing the walled garden problem has been the development of the so-called federative protocols for social media. In the last 10 years or so, a number of alternatives to the big social media platforms emerged, which together form something we lovingly call the Fediverse. Instead of a big company in the Bay Area running the social network for you, on the Fediverse you can make your own little social network, which then federates, i.e. seamlessly connects, with other people’s networks.

Your own network can have its own rules, visual style, settings and algorithms, but still be part of the larger ecosystem. The result is (in theory) a wonderful diverse mesh of services, which, importantly, cannot be controlled by any single organisation, let alone some fascist billionaire.

Mastodon has become a popular Twitter alternative, and has seen increasing adoption, especially since the Musk takeover of Twitter. Even the mainstream Twitter alternatives such as Bluesky and Threads have taken steps to open up to the Fediverse, showing that the model of open protocols is still attractive even for Silicon Valley types.

In practice, however, even the Fediverse is susceptible to the emergence of hierarchies. Mastodon has been suffering from the fact that most users don’t really care to run their own servers, and even when choosing servers, they tend to flock to the handful of really popular ones. Most Mastodon server maintainers don’t bother tweaking the user interface, so the typical Mastodon experience is still a flat, monochrome row of corn, not a thriving forest.

This is one of the fundamental contradictions of anarchist ideology: - Enabling systems that support individual freedom doesn’t necessarily compel individuals to exercise it. In a world built on hierarchies, freedom is something we must relearn and practice with dedication.

Less is more

The last resistance movement I’d like to mention is a bit more slippery and ephemeral. It hasn’t really had much consistent PR, a lot of people even in tech don’t know about it, and in some way it isn’t even a coherent movement at all. But to be able to talk about it, I will choose one incarnation of the idea: Laura Kalbag and Aral Balkan’s concept of Small Web.

Small Web (and its parent concept, Small Tech) starts with a realisation that all the organic material needed to create an apex Internet ecosystem already exists. While Silicon Valley techno-optimism teaches us to solve problems by rapidly throwing more tech at them, Small Tech asks us to pause and slow down. Could it be that we already have the tools to create a thriving and diverse Internet? Would we discover them if we just took the time to understand and use them?

Small Tech encourages people to use open protocols to create their own spaces on the Internet. In a way, it is a harkening back to Web 1.0, but it isn’t a retro aesthetic movement. It is about taking control of our Internet lives.

Small Web communities love and cherish the open protocols we’ve already had for decades. For fun, each year on HTML day, people meet and write Hypertext Markup Language together in parks and cafés. The HTML they write is owned by them and them only. They get to choose what it is, what it looks like and what it does, as well as where it is and who can access it. Every time a new piece of HTML is written, it becomes part of the evolving dialectic of the ecosystem - a unique constituent part, adding in its own way to the forest’s wholeness.

The Small Web sites are often extremely efficient and use a millionth of the energy needed to run the new AI startup’s landing page. They are fast and accessible for people other than urban creatives on beefed-up macbooks. They are often machine-readable and freely accessible to human and non-human beings on the Network, so they can be used for learning and for pleasure, even decades after the LLM companies that extracted their value file for bankruptcy.

Once the feudal system currently being put in place on the Internet collapses like a monoculture plantation after a storm, these things will persevere and rise again. Honestly, it's going to be fun watching what happens to our current hegemonic tech when the current AI bubble pops (well, fun, but also horrifying).

Platform, product or protocol?

The question remaining to be asked - in what ways can technology contribute to an Internet of Wholeness? Most tech companies these days begin by building an app, or a “platform,” and if they just go with the flow, they are likely to build another walled garden. At the same time, there are probably lots of people out there who would already find clever and organic ways to mesh their products into the Internet ecosystem.

Instead of suggesting answers, I would like this article to be more of a prompt for us all to think and discuss. This is why I’d like to conclude by asking in what ways could we be building a protocol, a language, a dialectical ecosystem instead? In what ways can we allow an oozy, endlessly-branching, uncontrollable climax forest to grow within its scaffolds?

Thank you for reading this Khôral Note, and see you next time!

Further reading

Murray Bookchin, The Ecology of Freedom. Available on libcom.org

Scott F. Gilbert, Jan Sapp, and Alfred I. Tauber. A Symbiotic View of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals. The Quarterly Review of Biology 2012 87:4, 325-341

Yannis Varoufakis, Technofeudalism: What killed capitalism. Available on archive.org.

Aral Balkan - What is the Small Web?