The Nocturnal Ground

Music, Negation, and Imagination A Dialogue Between Neoplatonism and the Kyoto School (Jam Sessions on Negation, Part 1)

Prelude - Jam Sessions on Negation: Framing the “Otherwise” in Khora

At Palinode, our weekly Jams are spaces where philosophers and technologists co-improvise: we test ideas, trade micro-lectures, and translate big questions into design prompts. Our first two October Jam sessions took on the philosophy and logic of negation with a product goal in mind:

How might Khora surface a “negative view”—i.e., identify nodes that stand in contrary, contradictory, or apophatic relation to one another—so users can see genuine opposition (not just loose irrelevance) and escape algorithmic echo chambers?

Each presenter offered a 15–30 minute angle that then sparked a build-focused debate about:

How might the values and uses of negation in the history of global philosophy be implemented into Khora’s superstructure?;

how could such approaches be supported through UI features?;

and how might users in turn challenge and improve Khora’s own work in this domain?

Over the next three weeks, you’ll hear from our Knowledge Ingest & Relation Curation Team—Dr. Sebastian F. Moro Tornese, Dr. Edward P. Butler, and Stephen Rego—with essays adapted from their presentations in the second Negation Jam Session (October 13, 2025). This week Sebastian will lead the way; in the next two weeks you will hear from Edward and Stephen. - Eli Kramer

Introduction

By bringing Neoplatonic aesthetics into dialogue with the Kyoto School—specifically Nishida Kitarō’s logic of place (basho / Nothingness) and Miki Kiyoshi’s logic of imagination—the following shall explore alternative approaches to reconciling key philosophical dualities via an unusual form of negation. In both traditions, oppositions between things like Being and not-Being, logos (reason) and pathos (emotion), coexist in a dynamic attunement grounded not in cognition alone, but in a creative space or pre-logical dimension of experience. This creative space is vividly illustrated in music, where silence, sound, and harmony shape an expressive interplay between self, world, and the ground of being. In each tradition, this resonance unfolds as an interplay and kinship (syngeneia) between subject and object, emerging through different forms of wielding and experiencing negation, something akin to ‘hearing’ silence, understood not as the absence of sound, but as a dialectical field of unfolding.

In Nishida and Miki, this musical unfolding can lead inquiring individuals into a state of affective and volitional attunement prior to conceptualization, where self and world mirror one another in the “basho of nothingness” (think Heidegger’s Stimmung in consonance with Hölderlin’s poetry).

In this context of an attunement prior to conceptualization, Neoplatonism favors a mythical and symbolic mode of expression, where the soul’s connection with the intelligible is awakened not through reason alone, but through the transformative power of pathos. While some Neoplatonic texts emphasize metriopatheia and apatheia (the soul’s integration and freedom from egoic passions), others turn toward inspiration and symbolic ascent, highlighting the transformative role of pathos as a vehicle for awakening rather than a disturbance to be overcome.

In these latter texts, pathē are not merely reduced to torybos—the tumult of becoming—but generate forces that awaken the ethical instinct, affinity with beauty and goodness, and the awe and joy accompanied with an epiphany or sudden vision. As Plotinus deems, this is the Intellect in love which resembles a form of “sober drunkenness”: a state in which the soul ascends toward the ineffable One, propelled by a desire for what lies beyond discursive thought, preserving therein its connection to the divine. This is a form of negation as it reaches after what lies beyond Being, reawakening an individual to the hidden unity within the One.

Similarly, Nishida’s notion of basho proposes an alternative, non-dualistic mode of reasoning appropriate to the ground of experience itself—one oriented toward immanent transcendence rather than transcendent immanence. Together, Nishida and Miki seek to articulate a rigorous logic of “place,” which Miki expands through the category of imagination to reconcile strict binary oppositions such as reason (logos) and emotion (pathos). This logic remains embedded in historical and phenomenological “everydayness,” while at the same time illuminating the dynamic relation between the concrete particular and the Absolute.

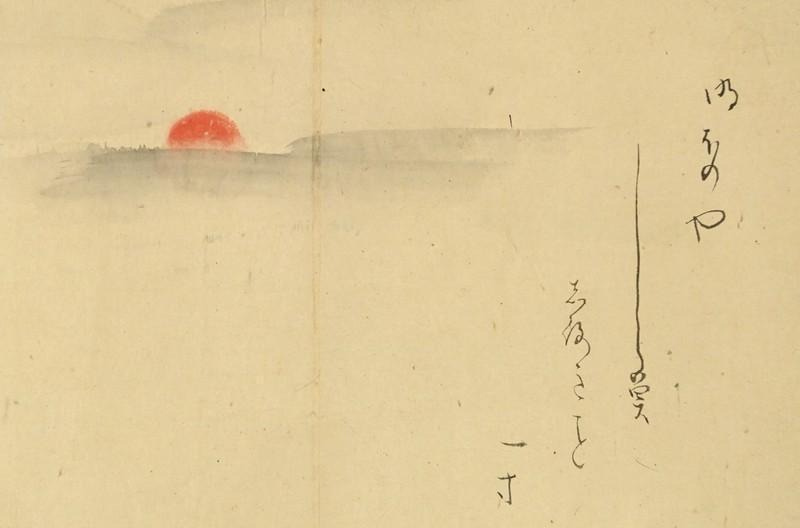

Overall, I hope to suggest that the ground of being is a kind of living silence and, as such, an ineffable source of sound, resonance, and kinship between self and cosmos. This unusual silence manifests itself musically, for example in the work of Tōru Takemitsu, who sought a subtle combination of tradition and innovation in a musical language grounded in silence and emptiness. In his compositions, the interplay of form and emptiness becomes the very condition for true innovation, which emerges not from mere novelty but from the depths of imaginative creativity

1. The Ineffable and the Orphic Nocturnal

In Neoplatonic and Orphic traditions, the divine is approached through negation and silence. The Greek verb ‘Myein’ — “to close the lips” or “to close the eyes”— marks the beginning of initiation, the gesture of entering mystery. Yet, to be clear, such negative theology does not aim at denying the reality of Being but, contrariwise, attempts to disclose Being’s depth and roots. As most are assuredly aware, this is a movement which goes beyond the limits of language toward what Plotinus and Proclus call the return to the One, the ineffable source of all. Like mindedly, Rilke, in his Ode to Music (An die Musik), poetically suggests that music is speech but, paradoxically, a speech testifying to its own limits:

“Music: Breath of the Statues. Perhaps: The silence of images. You, language where languages come to an end. You, time standing upright against the flow of vanishing hearts.”

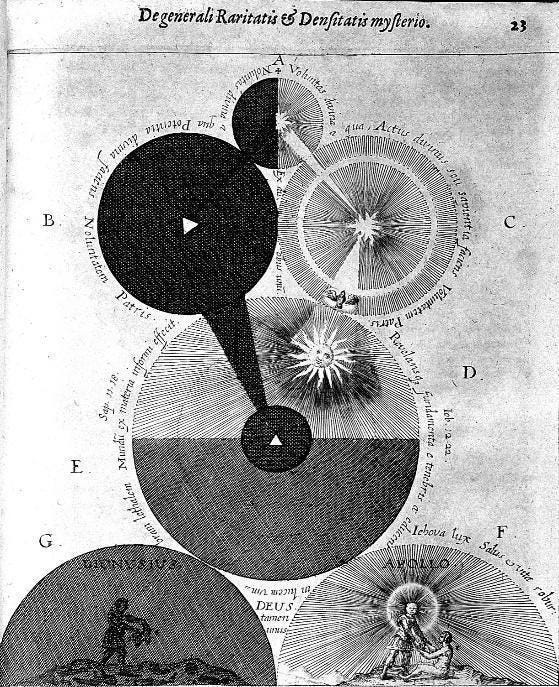

For the Neoplatonic/Orphic tradition, music becomes the noetic echo of the cosmos. Correspondingly, this echo resonates with Nietzsche’s conceptions of tragedy whereby one must witness the Apollonian stillness within Dionysian dance, the ecstatic nocturnal revelry which bears within itself an immanent silence. This silence does not arise from absence, but from music’s hidden ground: the dark, wandering womb from which all rhythm and harmony are born.

To ask a rhetorical question: what could possibly unite such varied works as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, Mahler’s Eight Symphony, and Scriabin’s Poème de l’extase? Put simply, each enacts a musical equivalent of negative theology: they move from sound to silence, from finitude toward the infinite, from the human to the divine, seeking, as Nishida will suggest in the next section, to hear “the voice of the voiceless.”

For Nishida, the passage from the formless to the formative and the formed is attained by a poiesis:

“The world is always one single present, moving from something made to something making. As a contradictory self-identity, the form of the present is the mode of production of the world. A world like this is the world of poiesis. In such a world, seeing and working are contradictory self-identities, and forming is seeing, and we can say that we work from seeing. We can say that we see things actively-intuitively, and that we form things because we see things.” (Zettai mujunteki jikodōitsu Section 2 [168])

This poiesis enacts a dialectic of movement and seeing: a Dionysian dance of reality and an Apollonian intuition of form. In Nishida’s logic, these are not opposites but contradictory self-identities—each shaping and shaped by the other, each revealing the world’s creative present.

Plato speaks about the poiesis of the Demiurge in the Timaeus, where the origin of the universe is depicted in mathematical and musical terms. In his Commentary on this dialogue, Proclus describes the Demiurge as acting from contemplative intuition, simultaneously in both the Dionysian and Apollonian manner: dividing the soul into parts and harmonizing them into a unified concord.

“To divide,” he writes, “to convey wholes into parts, and to preside over the distribution of forms is Dionysiac; but to harmoniously bring all things together into something complete is Apollonian.” (Proclus, In Timaeum II.197.15–30)

This dialectic of division and concord—of Dionysian fragmentation and Apollonian synthesis—becomes a metaphysical paradigm for the interplay between multiplicity and unity.

Mediated through thinkers such as Schelling, Schlegel, and F. Creuzer, these ideas reached composers like Beethoven and Wagner. In their conversations, Wagner and Nietzsche deeply considered these dichotomies and together reimagined Orphic–Neoplatonic themes as a dynamic interplay. This polarity finds renewed expression in Western classical and Romantic music—not only in the harmonic ratios that structure musical order, but also in the affective character of movements and forms.

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, for instance, dramatizes this tension: the second movement (Scherzo) embodies a Dionysian energy of ecstatic dance, while the third (Adagio) unfolds as an Apollonian vision of contemplative stillness, evoking the soul’s ascent toward the celestial. In the final movement, these forces are drawn together in a dialectical synthesis, anticipating the universal reconciliation that Romanticism sought to realize through music.

Consider also Mahler’s Third Symphony: it progresses from the earthly (first movement) to the vegetal (second) and the animal (third), before finding its existential center in the human response to the call of Night (fourth). From there, it ascends toward a climactic vision of the Heavenly and the Absolute. For the listener attuned to the score, this divine epiphany cannot be heard as a static “beyond time and space,” but as a dynamic eternal present, where music itself becomes a childlike renewal of love and playfulness.

To reinvoke Nietzsche, Zarathustra discovers here the wisdom and life of the feminine and the mysteries of the eternal return—through negation, self-overcoming, and the rhythms of Dionysian women dancing in the dark: a sacred time and dynamic space where all contradictions are gathered into one living clairaudience and resonance.

Music, within this Orphic (albeit with Nietzschean cadence) and Neoplatonic register, is not experienced as representational. Rather, it is a disclosive field that resists objectification and reification—a space where all components, but particularly one’s spirit, are transfigured.

For the Neoplatonists, this is the power of Absolute Life: a vibrant unfolding that transcends static being. The Orphizing Nietzsche, by contrast, anthropomorphizes this will into the fleshy image of Ariadne—the abandoned bride and ever-transformative consort to Dionysus. For Iamblichus and Proclus this Intelligible Life is expressed in the expansive character of the intervals of octave (represented by the double progression of the Timaeus) while the intervals of fifth represent the epistrophê and return, associated with number 3 and the triple progression (see Proclus, In Timaeum II.215. 5 - 215. 29). For this reason, for Proclus, the whole of reality is a dance and a musical hymn:

“For indeed the heliotrope is also moving toward that to which it easily opens and, if anyone was able to hear it striking the air during its turning around, he would have been aware of it presenting to the king [the Sun] through this sound the hymn that a plant can sing” (On the hieratic art/De sacrificio et magia 3, trans. Pachoumi).

2. Silence and the Logic of Place

This experience of the ineffable finds a profound echo in Nishida Kitarō’s notion of basho (place) and pure experience. The basho of absolute Nothingness is not a void opposed to being, but the ground of emptiness that allows being and self to arise in mutual self-negation.

“The absolute is truly absolute in facing nothing. By facing absolute nothing it is absolute being. […] That the self faces absolute nothing means that the self faces itself self-contradictorily. It is ‘contradictory self-identity.’ […] What stands against the self is that which negates the self; that which negates the self must share the same roots with the self.” (Nishida, The Logic of “Topos” and the Religious Worldview, transl. Yusa, Part 1,p.19)

The logic of place (basho no ronri) unfolds from the absolute basho, which creates connections by negating the objectification of the grammatical subject. The absolute — as place, pure experience, or eternal present — is a self-contradictory identity, a self-mirroring that manifests in the historical and embodied world that cannot be objectified. Nishida’s self-mirroring basho proceeds “from the created to the creating” (natura naturnas) and anticipates musical reflection as a mode of self-mirroring, linking human consciousness to the cosmos, its origins, and its generative ground in silence.

For Nishida, this Japanese and Buddhist approach to the Absolute is musical, poetic, and emotional — in contrast to the Western emphasis on image, structure, and logos. While music may seem formless, Nishida emphasizes how it carries a subtle shape — a “shape without shape.” His disciple Miki Kiyoshi extends this vision through a logic of imagination, proposing a creative mediation between intuition and structure, poetry and philosophy — a synthesis expressed historically in artistic institutions and, in our context, symbolically in musical instruments. The interplay between emotion and reason in Miki, and the mediating power of imagination, expands on Nishida’s view as expressed here:

“It goes without saying that there is much to be esteemed and learned in the brilliant development of Western culture, which regards form (eidos) as being and formation as the good. However, at the basis of Asian culture, which has nurtured our ancestors for thousands of years, lies what may be called seeing the form of the formless and hearing the voice of the voiceless. Our hearts cannot help but seek this, and I wish to provide a philosophical foundation for such a demand.” (Nishida, From Acting to Seeing, 1937)

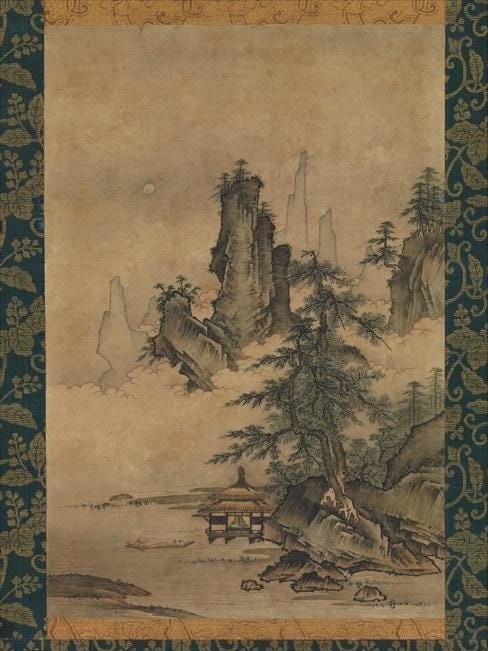

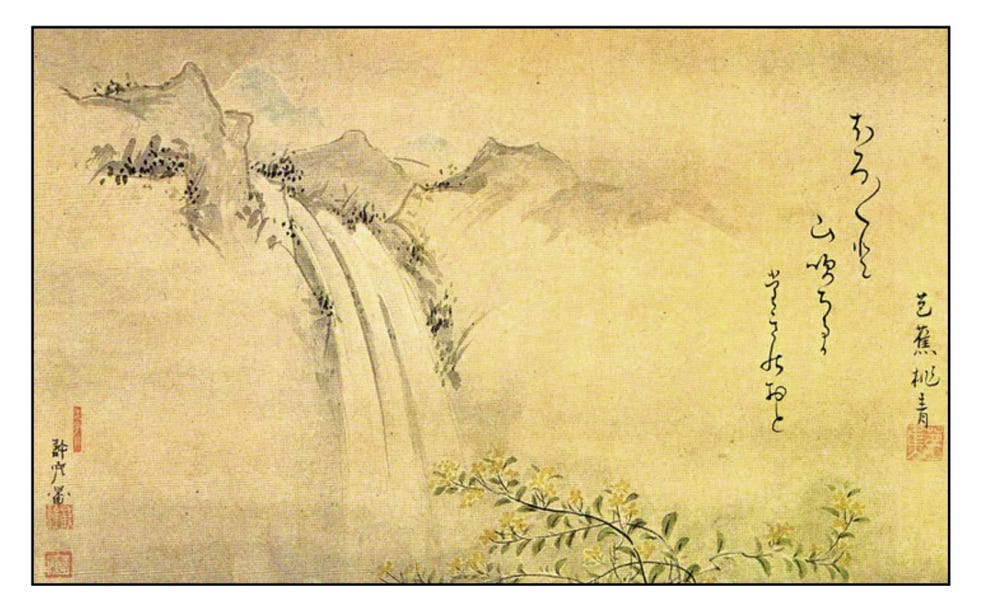

From this perspective, silence is not absence but resonance — the empty, breathing spaces (ma 間) between and within which sound lives and dies. In this sense, silence is not the negation of music but its generative ground: a field of emergence where difference unfolds without domination. Takemitsu’s music embodies this ethos. Influenced by Debussy, John Cage, and Zen, he sought to free music from the control of the subject, allowing sound to arise from the interplay of difference — not as imposed structure, but as spontaneous unfolding. The space between notes becomes integral to the music itself, like the shifting textures of a natural garden or park, where form emerges organically from stillness and breath.

The static and dynamic unify within this secret garden as Takemitsu’s Dream/Window evokes a stroll through the mossy landscapes of the Buddhist temple Saihō-ji (Kokedera). Likewise, in his Ceremonial, the shō (笙) — a Japanese mouth-organ — symbolizes the oriental Phoenix, the union of opposites, the celestial and the terrestrial, yin and yang, resounding in tune with Nishida’s logic of place. Takemitsu described his creative principle as “gathering sounds and gently putting them into movement,” avoiding domination and control, letting harmony emerge from its own ontological field, an audible basho. Echoing Simon & Garfunkel’s poetic phrase, “the sound of silence,” this aesthetic bridges parts of the Japanese tradition with Western innovation, marking therein the beauty of continuity.

3. Negation, Imagination, and the Poetics of the Ineffable

The Kyoto School inherits and transforms the logic of self-negation: for Nishida Kitarō, reality is grounded in absolute nothingness, where being and nothingness are no longer opposed. This standpoint is further developed by his disciple Nishitani Keiji, who interprets śūnyatā (emptiness) as the field in which negation discloses the true mode of existence. Nishida, in dialogue with D.T. Suzuki, appropriates Mahāyāna Buddhism and the sokuhi logic of the Diamond Sutra, contrasting this with Western substance. From the perspective of basho, beings are disclosed not as static objects but in their self-contradictory identity, so that reality reveals itself as compassionate harmonious unfolding, where being reaches it’s apex through self-negation.

Miki Kiyoshi’s logic of imagination and poiesis mediates between mythos and logos, grounding human creativity in historical and symbolic form. In Iamblichus, Proclus, and Miki alike, imagination functions as a mirror in which nature and self mutually reflect one another. When contemplating a lake, we become the lake, as consciousness and nature form a single field of pure meditative experience. Within this reflective depth, the Phoenix Hall of the Byōdō-in temple with its lake, the breath of the shō mouth-organ, and, for me, Thoreau’s image of Walden Pond as the “eye of nature” converge with the Neoplatonic vision of the World Soul.

Music exemplifies this mediation. Mahler’s Third Symphony, with its post horn call and nocturnal motifs, dramatizes the dialectical interplay between human longing and cosmic awakening. Takemitsu’s sound-gardens similarly enact a poetics of the ineffable, which is reconciled in the temporal play of memory and imagination, a dynamic basho in which subject and object, the emotional and the structural, converge through a continuous discontinuity. This unfolding is playfully made possible in the elemental imagery of water and gardens, where silence breathes and form emerges.

4. Toward a Shared Logic of the Ineffable

Comparing Neoplatonism and the Kyoto School reveals an alternative logic — one that unites reason and intuition, being and nothingness, expression and silence. Both traditions begin from negation, but their negation is a creative resource: the fertile darkness of Night, the silent ground of basho, the stillness from which music arises. These are structured by silence — by the breathing intervals of ma (間) and the reflective mediation of imagination and myth.

Music thus becomes a paradigm of non-dual gnosis and active-intuition: an experiential, ontological realization of nothingness as prior to logical articulation, revealing — paradoxically — the pre-linguistic unity of being and consciousness. Yet as individual souls, we require the vehicles of symbol, image, and art to manifest that ineffable source. From the Orphic hymns to Takemitsu’s Ceremonial, from the mystery in Mahler’s symphonies to the breathing pauses of ma, the ineffable place of Nothingness reveals itself as a living resonance — the invisible presence that moves, conducts, and harmonizes all things.

Bibliography

Bea, Nicole. Buddhism: The Way of Emptiness – True Emptiness, Wondrous Being. Blog on Buddhist philosophy, Zen, and the Kyoto School. Accessed October 2025. Available at: https://buddhism-thewayofemptiness.blog.nomagic.uk/.

Krummel, John W. M. Nishida Kitarō’s Chiasmatic Chorology: Place of Dialectic, Dialectic of Place. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015.

Lofts, Steve; Nakamura, Norihito; and Wirtz, Fernando, eds. Miki Kiyoshi and the Crisis of Thought. Nagoya: Chisokudō Publications, 2024.

Miki, Kiyoshi. The Logic of Imagination: A Critical Introduction and Translation. Translated and introduced by John W. M. Krummel. London/New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2024.

Morisato, Takeshi. “What Does It Mean for Japanese Philosophy to Be Japanese? A Kyoto School Discussion of the Particular Character of Japanese Thought.” Journal of World Philosophies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2016, pp. 13–25.

Moro Tornese, Sebastian F. “Neoplatonic Music and Ideas: Late Ancient Greek Philosophy of Music and its Reception.” Available at Substack (https://substack.com/home/post/p-150174591).

Nishida, Kitarō, and Michiko Yusa (transl). “The Logic of ‘Topos’ and the Religious Worldview: Part I.” The Eastern Buddhist, New Series, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Autumn 1986): 1–29.

Nishida, Kitarō, and Michiko Yusa (transl). “The Logic of ‘Topos’ and the Religious Worldview: Part II.” The Eastern Buddhist, New Series, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Spring 1987): 81–119.

Nishida, Kitarō. Last Writings: Nothingness and the Religious Worldview. Translated by David A. Dilworth. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1987.

Nishida, Kitarō.Zettai mujunteki jikodōitsu (Absolute Contradictory Self-Identity). Edited by Enrico Fongaro, Steve G. Lofs, Matthew D. McMullen, and Jacynthe Tremblay. Nagoya: Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture, Nanzan University, 2025.